Babylon (2022), the latest romp by Damien Chazelle of Whiplash and La La Land fame, was released on VOD on January 31 after a month-long run in theatres. As a result, the film has received an influx of viewers and, as is especially normal in our current zeitgeist, clips from the film have since circulated on social media sites, such as Twitter.

The clip that seems to have spawned the most conversation, however, is easily the film’s ending montage, which, among other things, features a supercut of various clips from films ranging through the decades, intermixed with clips from the film itself. Many have dubbed the scene pretentious, ridiculous, pompous, loud, et cetera. But I think this montage really, really works in part for the same reasons that people seem to hate it.

(The actual Twitter clip I’m referring to seems to have been hit with a copyright strike, so here is a shorter version of it — it chips a bit off the ending.)

It is no secret that I adore Babylon — I immediately sang its praises in December after viewing it in theatres, and have continued to do so. It’s also no secret that the film is an abject failure — it tanked at the box office, it’s been critically panned, and it garnered only three Oscar noms for costume, music, and production design — a far cry from La La Land’s six (actual) Oscar wins (and its near Best Picture win). Now, I believe that film, as with any other art, is largely subjective and that there is no shame in disliking a film, even vehemently and loudly — I do it all the time! But I do think that a lot of criticisms of the film really miss the mark. And the reception to that montage is quite an astute microcosm of such.

To understand this montage, it simply cannot be divorced from its context. If one were to watch this clip as most have, on their Twitter timeline as opposed to the chronological end of the actual film itself, it would read as potentially nonsensical. I can see how, from such a perspective, it appears as little more than Best Hits medley created by a self-proclaimed cinephile with access to Adobe Premiere Pro.

But.

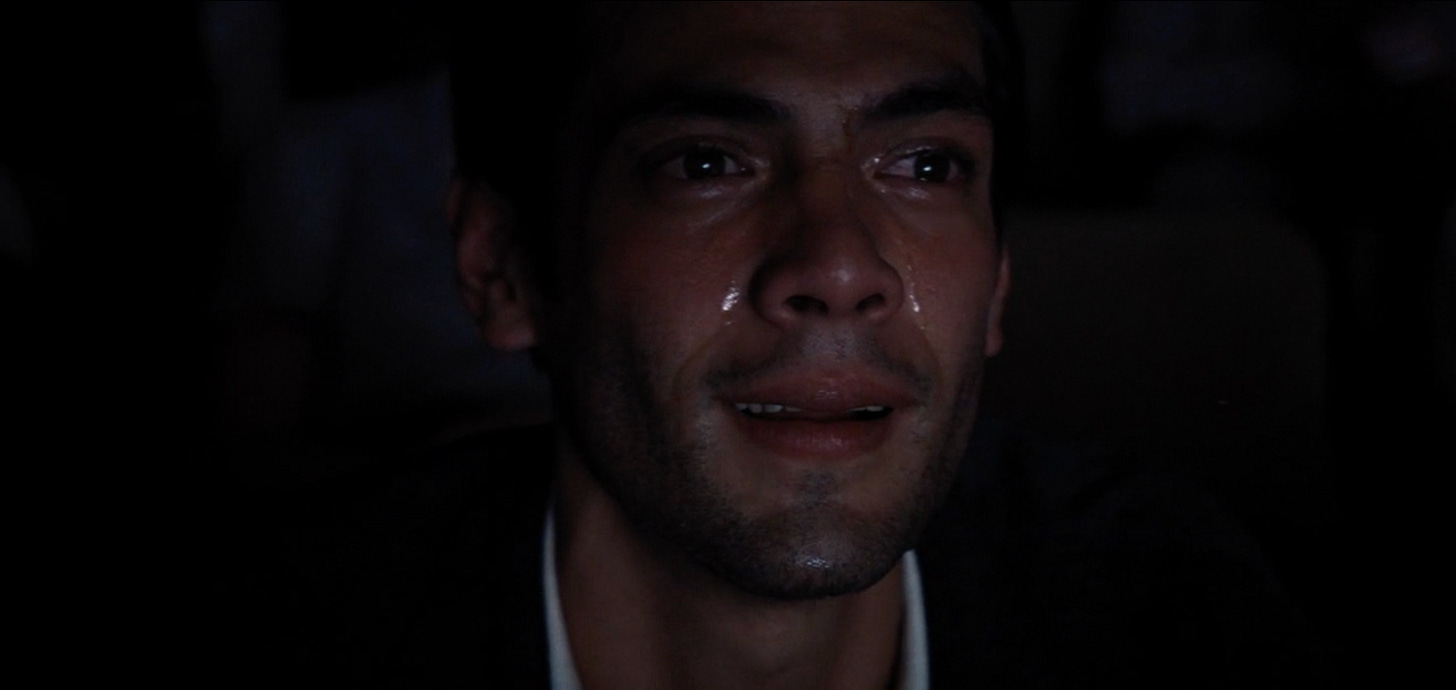

In the context of the story itself, this montage is preceded by Manny (Diego Calva) watching Singin’ in the Rain in 1952, years after he left the industry. Singin’ in the Rain and what it represents are integral to the ethos of the montage that is to follow. Manny enters the cinema to watch the film and falls asleep. And when he awakens, he is taken aback — as evidenced by the camera’s abrupt zoom and Calva’s own amazing facial acting (I maintain that he should’ve garnered a Best Actor nom for his performance) — to find that the events of the film directly mimic those of which he witnessed while working in Hollywood. In particular, the scene from the film wherein Lina Lamont sees a dictation coach is a mirror of the long-dead Nellie LaRoy (Margot Robbie)’s own inability to shed her New Jersey accent for the Transatlantic one that would become cinematic norm, which ultimately led her to spiral to her premature death. Manny becomes angry, gradually devolving into tears, at the fact that the woman he loved, who met such a tragic end, is being made a mockery of on-screen for people who never knew her. The camera zooms out and, for many minutes, surveys the audience around Manny, who are all watching the film without any knowledge of that which the film is based upon — or any intimate awareness of what goes on behind the screen at all, for that matter.

Many have deemed Babylon to be a love letter to cinema, an assessment that I don’t agree with. In my initial review of the film, I specifically decry such a description, instead deeming it an observance of film. And this distinction is what makes this scene, and the montage that follows, work so well. The montage isn’t simply a scene delineating how oh-so-amazing film is, but a recognition of the feats in cinema and the fact that cinema continues, flourishes, and advances despite all of the unsavouriness that makes way for its innovation. This recognition of the paradoxical nature of Hollywood — and of any industry under capitalism, really — and the fact that by revelling in its innovation we are simultaneously if unwittingly, celebrating the exploitation and injustices that made way for it to come to fruition, is at the crux of this scene, and this film. Therefore, if anything, it’s more of a condemnation of Hollywood and of cinema than it is a love letter.

Notably, the montage is bookended by shots of Manny and his peers — Nellie LaRoy, Lady Fay Zhu (Li Jun Li), Sidney Palmer (Jovan Adepo) — all of whom either died or whose careers died, and in most cases for reasons above them: Lady Fay Zhu is ultimately fired as a title writer due to her sexuality, Sidney quits working with Kinoscope after he is asked to use makeup to darken his skin. Of course, those reasons above them are orchestrated by none other than Manny who, under pressure from his higher-ups at Kinescope, fires Lady Fay and requests that Sidney wear the makeup. Manny is not only lamenting the terrible things exercised by Hollywood, of which Singin’ in the Rain both triggers and represents, but his own hand in said things.

Then there’s the choice of film clips featured: the bulk of The Horse in Motion (1878); the infamous eye-cutting scene from Un Chien Andalou (1929); a shot from A Trip to the Moon (1902); the scene in the Wizard of Oz (1939) when Dorothy finally enters Oz; a glimpse of Avatar (2009), to name a few. Now, these aren’t simply clips from infamous films, but clips that correspond to movies that completely changed the cinematic game. The Horse in Motion is believed to be the first film ever made; A Trip to the Moon is considered to be the first science fiction film ever made; Robert Ebert dubbed Un Chien Andalou the most famous short film ever made, with that eye-cutting scene an unabashed marvel of early practical effects (the eye is a calf’s eye, don’t worry); The Wizard of Oz — while not actually the first colour film as is largely believed — is nonetheless one of the first, and surely the most infamous early Technicolour picture; and Avatar is known for its groundbreaking 3D technology.

The selection of such game-changing entries into film, bookended by the implications of aforementioned scenes, and precipitating Manny’s deeply emotional response to his viewing of Singin’ in the Rain, elucidates the paradox of cinema, the fact that such innovation almost certainly succeeds exploitation and dehumanization and discarding. Any perceived beauty of cinema, this film seems to want us to reckon with, is brought to fruition at the behest of incredible ugliness.

Such elucidation is punctuated further by the crass quality of the montage; the images are increasingly discombobulated, the score exponentially cacophonous until neither the images nor sound make much sense at all anymore. The montage is an overlong, repulsive sensory nightmare. And that’s the point. Because cinema is similarly messy and loud and sad and rapturous and, while predicated on a fraught history, is able to continuously and effectually move us to discuss, to think, to rewatch, ad nauseum. The industry that killed Nellie LaRoy is the same industry that continues to thrive and transform audiences, in spite of. Because of.

And that’s why, at the end of the montage, as Manny looks at the screen with tears still in his eyes, he is able to smile.

god I loved Babylon the interpolation of La La Land's score into *that* scene made me smack the leg of the person next to me in the theater (much to his horror: he didn't know me)

The distinction that it is an OBSERVANCE of film !!! You understand it !!!!