With the recent release of The Hunger Games prequel, Sunrise on the Reaping, the dystopian series has reentered public discourse, reigniting at least a degree of the fanaticism that once followed it in the 2010s amidst the release of its film adaptations.

I pre-ordered this book in the early months of 2025 and promptly received it on the evening of its release. I finished the book in less than two days, not because it was any good, but because I’ve always been a fast reader. To be absolutely crystal clear: I hated it.

I was, and continue to be, a big fan of the original Hunger Games series. I endeavoured to read the first book at the age of eleven, about four years after the book’s release, upon the suggestion of my fifth-grade teacher, Ms. Clifford. I was immediately hooked; I flew through all of the books. Every book-related presentation or report I was assigned thereafter was dedicated to one of the books in the trilogy (for a book report of Mockingjay, I dressed up in grey in an attempt to mimic the inhabitants of District 13). And this obsession only grew with the announcement and ultimate release of its film adaptations; I made my mother purchase every companion piece, poster book, and essay compilation that was released and read them with the same fervour as I had the trilogy they spawned from.

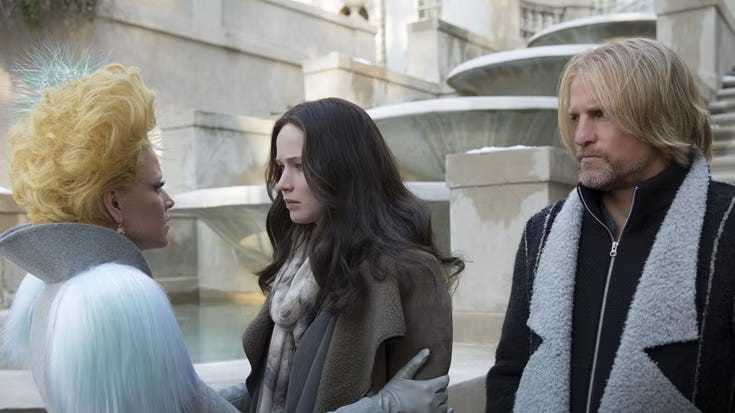

But, by the last film’s release, my fanaticism had ebbed. The books and films continued to hold a significant place in my heart, nonetheless—I watch Catching Fire yearly—but my ardour had been abated. I know fourteen is nothing resembling close to old or mature, but at that point, I had transitioned to engaging with more advanced literature. I think, as much as I still loved the material, I recognized it for what it was: a well-written, but ultimately elementary, series about oppression and rebellion.

I didn’t read the prequel, The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, until four years after its release, and only then so that I could engage with the film adaptation in an informed way. I quite disliked both, a dislike that led to a steep degree of disillusionment. Had these works always been so poorly written and conceived? So trite? A return to the original trilogy a few years later, amidst three months of unemployment in early 2025, assuaged my worry that this was the case; the original series still held up if taken for what it was: again, a well-written, if elementary, series about oppression and rebellion.

So, I decided I would give the new prequel a chance. I didn’t like Ballad, and although the majority of my issues with the story were technical as opposed to the result of its focus on a character whose lore I cared little about, I hoped, somehow, that Sunrise’s focus on a character I did like, if nothing else, would make it of relative intrigue. However—unsurprisingly—I was wrong.

I do not merely dislike Sunrise, I despise it. My stomach turned against it mere pages into reading, a distaste that only grew as I continued. The book garnered several visceral responses from me throughout its duration: eye rolls, sighs, and ironic laughs. It’s everything I disliked about Ballad amplified.

The prose is juvenile and clunky, with elementary and redundant phrases. For instance, Haymitch frequently uses the term “all-fire” to describe the degree to which he likes something—as in, he loves his girlfriend, Lenore Dove, “like all-fire.” Why Collins thought this sounded good is anybody’s guess. The pacing is strange, mitigating every potential emotional beat and eschewing any possibility of suspense. As such, the Games, the deaths, and the traumatic aftermath feel completely without stakes. The language, as well as the messaging, is so overt and banal as to be ineffectual. The actual story is preceded by a four-fold epigraph consisting of the following quotes, effectively spelling out its thesis:

"All propaganda is lies, even when one is telling the truth. I don’t think that matters, so long as one knows what one is doing and why” – George Orwell

“A truth that’s told with bad intent / Beats all the lies you can invent” – William Blake

“Nothing appears more surprising to those who consider human affairs with a philosophical eye than the easiness with which the many are governed by the few, and the implicit submission with which men resign their own sentiments and passions to those of their rulers. When we enquire by what means this wonder is effected, we shall find, that, as force is always on the side of the governed, the governors have nothing to support them but opinion. It is, therefore, on opinion only that government is founded, and this maxim extends to the most despotic and most military governments, as well as to the most free and most popular” – David Hume

“That the sun will not rise tomorrow is no less intelligible a proposition, and implies no more contradiction, than the affirmation, that it will rise” – David Hume

Drusilla, the pre-Effie escort for District 12, routinely calls the District 12ers pigs and, in a fit of rage, beats Maysilee with a riding crop. Haymitch is hoisted up in a cage at a post-Hunger Games party following his win, where the Capitolites in attendance feed and pet him through the bars.

The story brims with shoehorned cameos from the original series in the interest of fan service rather than narrative or thematic relevance, let alone continuity. Mags, Wiress, Beetee, and Effie all appear in this for some reason; Mags and Wiress are Haymitch’s mentors, Beetee the mentor of District 3 (one of the tributes for which is his son, thrust into the Games in order to punish Beetee for his sabotaging of the Capitol’s telecom system), and Effie is the sister of one of Haymitch’s stylists. If that’s not enough, we discover that Haymitch was actually besties with Katniss’ dad (here, revealed to be named Burdock, who is already courting Katniss’ mother, Asterid March)! And Plutarch Heavensbee? The director of all footage of The Hunger Games and its ultimate propagandist. While it isn’t outright incongruous that Haymitch knew these individuals so intimately, it is rather hard to believe. Nobody in the notoriously small District 12 let slip that Haymitch, Katniss’ dad, and Katniss’ mom were friendly? I’m meant to believe that despite Mags, Wiress, Beetee, and Plutarch allegedly being co-conspirators in a rebel plot, Snow let them all live and, in the case of Plutarch, without even a scratch to show for it? I’m just not buying it.

Then, there’s the issue of the nonsensical plot. First, there’s the revelation that Haymitch isn’t reaped at all; the boy who initially is reaped is killed by Peacekeepers after attempting to flee and, in the proceeding scuffle, Haymitch is ultimately selected to take his place. The implication that the Games have been rigged flies in the face of a very important aspect of the original plot and of the Games themselves, which is that the reaping is completely up to chance. Just like that, the gravity of Katniss’ being plucked from the masses and becoming the inadvertent symbol of the revolution is rendered moot, retroactively posturing Katniss as the Chosen One, which once again flies in the face of the message of the original series. On that end, secondly, there’s the book’s rebel plot. For whatever reason, Beetee and Plutarch decide that Haymitch is the perfect person to enact such a scheme in the arena: to blow up the tanks of water in Sub-A, a second control centre under the arena, effectively drowning Sub-A, (which is supposed to, but doesn’t, stop the Games), which he executes with ease.

There’s also the fact that Haymitch faces virtually no adversity in the arena: every dangerous mutt he encounters (including a random giant porcupine that appears and then leaves rather unceremoniously?) seems to be programmed to attack people who aren’t him; a bunny miraculously appears and dies after drinking from a stream just in time for Haymitch to realize that the arena’s food and water are poisonous; he’s saved by Maysilee before a Career can kill him; and, despite being sliced up enough by the runner-up of the Games to have his intestines spill out of his stomach, he still manages to last long enough to create a bomb and throw it into the forcefield under the cliff he’s at the top of and, also manages to survive with no injury.

And, then, of course, there’s the problem of Haymitch himself. All of the characters presented in this are one-dimensional, emblems of singular characteristics or cliches, with even the characters we know from the original trilogy being dumbed down (Maysilee is actually tough and kind, despite being rich; Wyatt gambles; Beetee is soooo smart; Snow is soooo evil; Mags and Wiress are nothing at all). But, the greatest offender is the novel’s protagonist. There is virtually no semblance of similarity between the Haymitch of this book and the character we’ve known thus far. Yes, Haymitch indeed becomes hardened as he spirals into alcoholism, but surely, there should be some resonance between either depiction of the same character. Besides, the issue with Haymitch’s characterization isn’t so much that it’s inconsistent as the Haymitch of Sunrise bears no discernible traits. His voice is nondescript, his feelings untenable. It’s as if his entire characterization—as is also the case of much of the novel—subsists upon the hope that the reader will somehow fill in the obvious gaps.

The book’s ineptitudes, its reliance on nostalgia, and its belief in the audience’s pliability were so glaring to me that I was sure the reviews of the novel would be overwhelmingly negative.

Once again, I was wrong.

The messages were very clear, which is needed right now given the utter lack of media literacy! Haymitch is 16 years old, so it makes sense for the prose to be a bit juvenile! The plot contrivances make sense because they show how messy the games were at this point! It’s not fan service that a handful of characters from the original series randomly appear in this one, effectively retconning the events of said trilogy in their entirety, or that hardly any of these characters act in a fashion that is congruent with their established characterization! These are just some of the excuses that have been put forward to explain why the book is good, actually.1 And, they irritate me immensely, not simply because I disagree with them, but because they point to a rather ridiculous predominant assessment of the series, which is that they are somehow singularly profound revolutionary texts.

Does the original trilogy put forward poignant and even aspirational ideals about countering adversity? Sure. Does it do so in a relatively intelligent and nuanced way? Also, sure. But even at its best, these books are not theory, and they’re certainly not praxis. And, despite admitted poignancy, their politics aren’t irrefutable.

Collins does not know how to handle characters of colour, for one. She spends every single book, including the prequels, dedicating a significant amount of pages to remarking on how big, strong, imposing, and virtually inhuman the Black characters that crop up are.2 Thresh is described as a “physical giant,” and portrayed as brutal and unfriendly (funnily enough, in this regard, the films humanize him a tad more).

Mockingjay, while one of my favourite books in the series, especially displays the extent of Collins’ lukewarm politics. For one, it often reads as Red Scare propaganda; it’s not hard to find resonance between its depiction of District 13 and its malignment and misrepresentation of communism, with that of Western media’s portrayal of Russia or China. But, perhaps most salient of all is its pacifism. Yes, Panem goes to war and it’s through this war that the Districts are ultimately freed from the Capitol’s imposition, but the book reiterates that if the oppressed react to their oppression with violence, while potentially justifiable, nonetheless renders them as bad as their oppressor. The representation of this is primarily funnelled through Gale, whose violent fury in response to his immense poverty is vilified and dismissed. In fact, in a conversation between him and Katniss, Katniss claims that his insurrectionist sentiment is tantamount to that of the ethos of the titular Games.

To that end, I take further and ultimate issue with the way Suzanne Collins—a white woman and the daughter of an American military officer who served in both Korea and Vietnam and, who, in the acknowledgements of Mockingjay, is credited as “[laying] the groundwork for [the] series” —has been postured as a revolutionary thinker. I fail to understand what credentials Collins possesses for fans to have deified her as the mouthpiece of anything remotely radical, to purport that she “only writes when she has something to say,” to bolster the something in question as gospel.3 As good as one might believe her works to be, nothing that Collins writes is innovative, and it is a condition of her whiteness that she is so actively defended and lauded. I don’t see the same clamouring en masse to lionize Octavia E. Butler, for instance, for her often-prescient dystopia Parable of the Sower, despite its sequel astutely predicting the adage of “Make America Great Again” back in 1998.4

I do not think there’s anything wrong with liking any of Suzanne Collins’ books or believing her to be a good writer, nor do I think there is anything wrong with loving Sunrise on the Reaping. But, I do believe that the uncritical analysis of her works and the idolization of her portend something childish at best, and disconcerting at worst.

Toward the end of Mockingjay, one of its characters cites the metonym of “panem et circenses”; translating from Latin into “bread and circuses,” which refers to those in power placating the masses with entertainment to distract them from the problems that are at hand. How ironic is it, then, that this series has become the very thing it critiques, and those who so stan it are none-the-wiser?

Severely paraphrased, and without reference, of course, because all things considered, I do not think stupidity warrants cancellation.

Save for Rue. But the exception doesn’t disqualify the rule.

Allegedly, Suzanne said this about herself, the evidence for which I have yet to find. Even if she did, however, the argument still stands as to why people should take this at face value.

The argument can be made that people aren’t hyping up its series because it’s not contemporary. To that, I say 1) you are ignoring the entire premise of the argument and 2) if you are an adult who does not engage with material written before the 2000s, there is absolutely nothing for us to discuss with each other.